Thursday, 24 April 2008

Part 5 - The Catastrophic effect - A retrospective account

Brandy slid down my throat, burning a path through my oesophagus on the way to my stomach. I shuddered at the hot harsh taste from a drink I was none too fond of. John had poured large measures and in the absence of anything else alcoholic, it would have to do for now. He raised his glass looked at Mark and me and said, “Cheers, here’s to the old man, God bless him, and to uncle Iain too. May God welcome them even though they were a pair of toerags from time to time!“. He threw back his head and gulped a large amount of the brandy before walking towards an armchair and flopping down like a rag doll. The last few weeks of misery were etched on his face; gaunt with dark circles beneath cheerless blue eyes. I felt his pain as I watched him struggle with his exhaustion and grief.

“How are you John?”, I asked, desperate to know how he was coping. He ran his hand through his dark brown hair before knocking back another large gulp of brandy. He looked past me staring vacantly into the distance. For a moment I thought he was going to cry but he stood up, strolled over to the brandy bottle and refilled his glass with a four finger deep measure. I wanted to caution care but this was no ordinary time for us, no run of the mill situation and “if you couldn’t have a drink now then when could you?”, I asked myself.

Leaning his arm on the mantelpiece, he turned towards me and finally held my gaze. “I feel like hell, Mob. It’s been a nightmarish two weeks, a real rollercoaster of emotions. Dad was still a grumpy old bugger but he was scared and that was hard to watch. I wouldn’t wish it upon anyone to watch a parent die like that, no matter what they’d said or done in life".

“I’m sorry and I know this is still very raw for you, but how was it, how did he cope at the end?” Perhaps it was morbid of me, kind of like rubber-necking at a road accident but I felt it was important for me to know the details so I could empathise with him, get the complete picture of just how awful it must have been for him and dad.

John walked back to the armchair, placed his drink on a side table and sunk down into the drab and uncomfortable burgundy leatherette chair that had been my father’s favourite for twenty years or so. I’d only seen my father once in this apartment some two years before, sitting in the same chair that John now occupied. It had been a short and depressing visit made out of guilt that I hadn’t seen him in such a long time and made out of curiosity to see just how he had faired and if there were any changes, regrets, apologies. I’d been shocked and saddened to see him try to warm his hands by the side of a clothes iron that he would plug in for that very purpose for he couldn’t afford to have his gas fire fixed. So much of what I felt for him was a complex set of emotions that ranged from hatred to pity but never love. But that day I felt compassion for a man haunted by his addictions; a victim of his learned behaviour from his violent father before him and a victim of circumstances borne out of a rough Glaswegian culture that endorsed domestic violence as almost a right-of-passage for a generation born at the time of the First World War. I had his fire fixed and paid his quarterly heating bills thereafter; I didn’t love him but neither did I hate him anymore; I couldn’t walk away and leave the man to freeze for the rest of his life in a city that was on the same latitude as Canada and frequently published record low temperatures. He got practical help and money from me in lieu of love.

His appartment was alien to me; he’d moved here long after I had fled the family home at fifteen to go and stay with a friend so I could continue my studies in my attempt to make a better life for myself. The apartment smelled of neglect and I felt sorrow for a life not well lived that had ended in an alcoholic haze, in pain and isolation from his family. There was a hollow echo to our conversation as though there was nothing of substance, no warmth here to cushion the sound of our words. It had a forlorn and desolate atmosphere with threadbare rugs placed on the dusty floor that was covered in cheap cracked linoleum where grimy ancient floorboards peaked through. The bare light bulb hanging from the nicotine stained rose holder in the ceiling streamed out naked light and cast strange shadows on the grubby and torn wallpapered walls of the room. The thick aroma of stale beer and cigarettes hung heavily in the air, a testament to the lifestyle that had brought my father to his knees with lung cancer. Years of his own disregard for his comfort and welfare were evident everywhere you glanced. A quick inspection of his kitchen had left me breathless; it was so dirty it should have been condemned and if the cancer hadn’t carried him off then surely to God, Ecoli would have done for him instead. A swift examination of his cupboards found no food for his consumption but instead offered up a bizarre collection of empty scotch bottles, about a hundred in total. For why he had started this strange collection, I do not know. My rapid troll through his apartment told me all I needed to know of the man of late; squalidness, neglect and loneliness reeked from every aspect of his small home. I suddenly felt deeply ashamed and sorrowful that his life had come to this; living with no real pride or respect for himself, no apparent signs of care and attention by himself or from anyone else.

“John?”, I turned my face back towards my brother to prompt him to come back at me; to at least try to relate some of those two weeks with dad. That way I could spare him a bit and share his narrative with our brothers and sisters as they arrived to ask the same questions over and over.

“Sorry”, he apologised. “I was watching you scan the room; you’ve got the same shock and disgust on your face that I must have had when I saw it two weeks ago. That’s the reason I was here in the first place”, he offered, as the start of his narrative as to how it was he who happened to be here in Glasgow with our dying father when he usually lived down south like me.

“Christ John, the place is a dive, a bloody squat. I don’t remember it being this bad when I saw him two years ago”. I wondered if perhaps his death had suddenly made me look much more closely at everything; brought things into a stark reality that I couldn’t hide from.

“Exactly what I thought Mob. I couldn’t believe the deterioration in the flat and in him either. But there’d been a flooding from the apartment above and from what I can gather he’d just left it, didn’t bother to sort it out at all. That’s why the place smells so musty”, he offered, as an explanation for the shambolic environment we were sitting in. I nodded my head in agreement because the all engulfing smell made me feel I’d develop consumption if left to wallow in such surroundings for more than a day or two. It was no wonder why the doctors had diagnosed pleurisy when my father was first admitted to hospital.

“Dad called me out of the blue”, he continued, “asked me if I had a couple of weeks to spare to come up and help him decorate. As I was between jobs, I thought what the hell. A couple of weeks in the old homeland would be just what I needed to stave off the boredom until my next contract started. But I knew when I saw him, he was clearly very ill and that the decorating plea for help was his way of getting me here to help him. He never said it but I’m sure he knew it was serious, had probably been in pain for months and only decided to do something about it when it was too much for him to handle”.

“Oh dear god almighty John, what must he have gone through being isolated and scared like that for him to have finally sent out a distress call to you?”, I said, more out loud to myself. “It’s not as if you kept in touch that often is it?”, I asked, looking at him for confirmation or denial that he’d been a better child than I had been.

“No, you’re right. Our contact was sporadic at best so I was as surprised as you are that he made the call”.

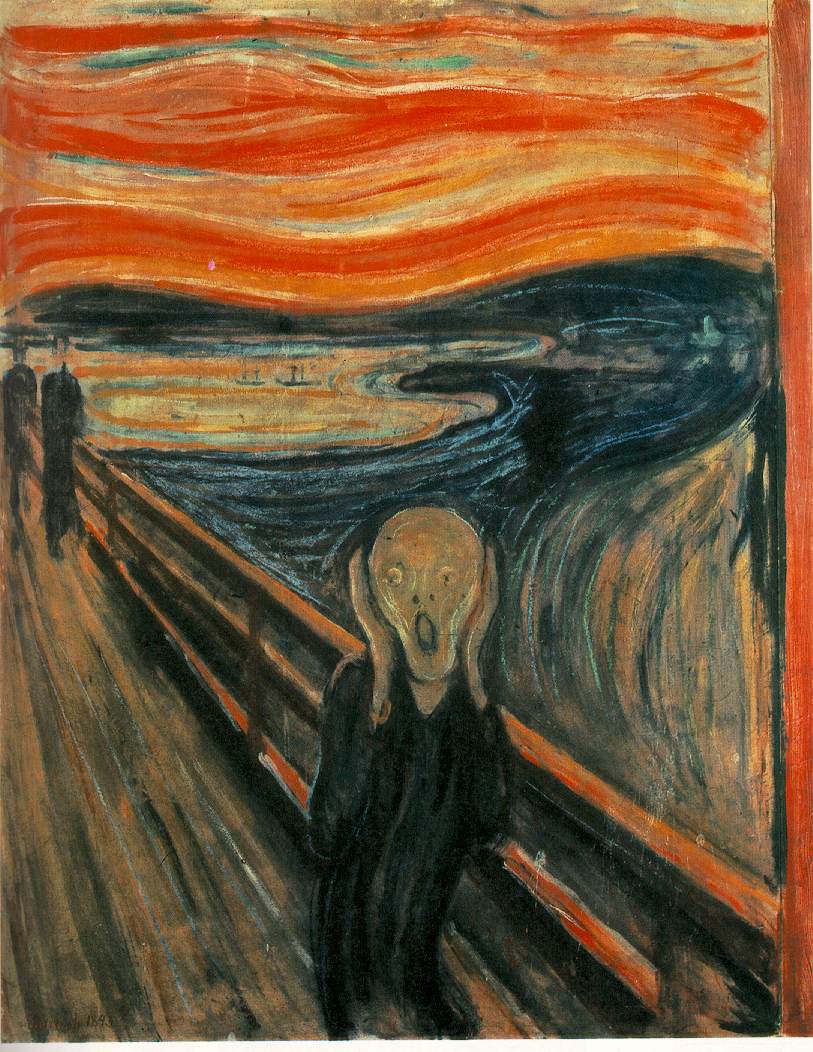

Trying to imagine Dad’s last few weeks of loneliness and terror was like a bolt of lightening to my heart. I closed my eyes to steel myself because I was so deeply mortified that I had let my father’s life come to a close in such a way. The if’s the if’s the if’s......If only I had known, if only he had said earlier, if only I had cared.... They went on and on pounding my brain but it was futile to think what if? But you do it anyway.

“And so”, John carried on, “I got here albeit under false pretences, realised what was going on, got him into hospital and the rest is history. I called the family, let everyone know the regular updates and sat and waited, just waited because there was nothing else I could do. The old man was in and out of consciousness until the last few hours but at least the morphine kept the worst at bay. He was delusional from time to time but he was compos mentis for enough of the time he managed to spend with Alex", he said in conclusion.

“Alex, Alex is here? Where on earth is he then?", I asked in astonishment for I hadn’t even considered that any of my other siblings had made it home.

“Oh, Christ I thought I’d told you. He turned up yesterday afternoon. He’s off picking up dad’s clothes and other stuff from the hospital. They asked yesterday that someone come in and do that today. Thankfully Alex offered to do that for I have seen enough of that place to sicken me for the rest of my life”

I was relieved that John had not been alone when my father passed away and appreciative that Alex had made it home so dad could see another of his son’s in his final hours. With that thought, my brother Alex walked into the apartment. I stood up and we walked towards each other finally culminating in a tearful hug of brother and sister lamenting the loss of a parent.

Now there were enough of us present to start the planning of the funeral of a man, a father, who had been robbed of us in life by alcohol and now had robbed us again with his death.

Wednesday, 16 April 2008

Part 4 - The Catastrophic Effect - A retrospective account

After a simple breakfast consisting of coffee and toast and an emotional hug of the cat goodbye we started our journey north to Scotland. The deaths of my father and of uncle Iain last night have left me feeling raw and confused and naturally somewhat subdued. Mark has insisted on doing the driving for I am too distracted to be safe behind the wheel of a car. Once again I was thankful for the strength and kindness of this man and how he’d marshalled me along since returning from Minneapolis.

As we speed along the m1 and m6 motorways, I think about the scores of times that I’d undertaken this journey; times when the excitement of seeing family and friends was palpable and uplifting and my heart soared for they were sorely missed. A deep homesickness had been prevalent in my early years away and I was never happier and with a real lightness of heart just to know that in a few hours we would be in the land of tartan, clean air, more mountains than you could shake a stick at and sharing sharp banter with a population of natural comedians.

My home city of Glasgow had the dubious moniker of ‘home of the deep fried Mars bar’; I’d never eaten one but I had no trouble imagining the combination of sickly sweet caramel, fondant and chocolate encased in a greasy batter and knew it would be enough to make me heave up the lining of my stomach. This atrocious concoction, loved by many, was swiftly followed in popularity by the deep fried pizza. Cleary ingesting both these delicacies on a regular basis was a death by clogged artery suicide; but that’s Glaswegians for you, the constitution of an ox with an attitude of ‘manyana’ to all things risky in life.

“Aye hen, a’ll gie it aw up the morra when a’m no sae pished and hungry”, was a popular retort of many a drunkard when challenged by some sour faced auld biddy feigning disgust at the inappropriateness of the drunk man’s evening repast. It could usually be relied upon to be followed up by a quick aside of “An’ away an sort that sour auld face aw yours oot cause a’ll be sober in the mornin’ but you’ll still look like the fecking grim reaper huvin a bad night oot, mrs. Ah sure hope you're no married ‘cause God help the poor bugger if he’s huvin tae wake up tae that old fisog on a daily basis”, he would lob as a parting shot, with grease drippin' doon his chin.

The warm and down-to- earth attitude, the simple cheek and the never short of a quick retort of Glaswegians makes for an abundance of humour in everyday situations and life. Although a city, Glasgow could easily be a big village for everyone knows everyone or at least will know someone who knows someone who knows you, if you get my drift. Talk about six degrees of separation - in Glasgow it’s more than likely three. And you can’t stand at a bus stop for someone telling you a tale or if the bus is long enough in coming, their whole life story. It is well known that most Glaswegians suffer from the same affliction to talk the hind leg off a donkey for we are genetically predisposed to do so and it is this that I miss most since leaving home; well, that and someone peeling open a well wrapped paper poke, (bag), that wafts out the tantalising aroma of volcanically hot freshly cooked chipped potatoes doused in salt and vinegar and calmly seeing if, “you want wan hen?”, as he/she pokes the bag in your direction. No one is a stranger for long in Glasgow, no one, irrespective of colour, creed, shape or size.

Reminiscing about my clan folks and their ways fills me with warmth and a deep appreciation of home and I smile for the first time in an age. It is a magic place to be. I feel comforted and slowly relax back into my seat, close my eyes and find the gentle hum of the car soothing.

Normally my natural ebullience at heading home would have me playing my favourite songs at top whack whilst I willed every hour on the road to be a minute so that I could be home sooner. Sometimes I flew home for the occasional long weekend when time was of the essence. But mostly we drove home for there was always a list of food orders as long as my arm to bring back to the Scottish diaspora exiled down south in search of better paid jobs and careers. On those return journeys back to England the car boot was laden with the type of Scottish fare that we had grown up eating and taken for granted but had since become manna from heaven purely because they were unavailable outside of the Scottish borders.

For months after returning home to England we could be found snaffling rare Scottish treats such as neeps and tatties, bridies, mince and dough balls, square, (Lorne) sausage, tattie scones, Scottish plain and pan bread, bread rolls, Scottish steak and sausage pie, Scotch pie, clootie dumplings and black pudding. Several generations of Scots had been reared on this stuff and as wains, (kids), it stuck to our ribs and gave an extra layer of protection from those bitter north winds that would whip around our wee bodies as we ‘played ootside tae gie oor mammies peace and quiet fur a wee while’.

But what of the legendary Scottish haggis you might ask? Well, you could stick your haggis as far as I’m concerned; to this day I can’t imagine swallowing and keeping down a pile of sheep’s innards cooked in a sheep’s belly. It’s no great mystery to me that you need to down a quick shot of scotch after you swallow a mouthful of haggis; you require it to quell the need to propel it rapidly across the room as your belly rejects it in record time. It’s no wonder that every time I see someone projectile vomiting I assume I am witnessing them having their first and last taste of haggis. It’s a common fallacy that just because you are Scottish you will be eating haggis by the poundage and feeling all the better for it.

I certainly fare no better with shortbread either. About a ton of flour, at least a block of butter and a pound of sugar creamed together and baked with millions of fork pricks all over it then left in a tin for months to dry out; it has no trouble lodging itself firmly in my throat. It’s handy if you want to shut me up for a while - and many do - because it totally sucks every piece of moisture from my mouth and it takes at least a pint of liquid to rehydrate it again.

Still, haggis and shortbread aside, “everything in moderation”, and “a little of what you fancy does you good”, being the cries of the war baby generation of our parents so we take heed and limit ourselves to scoffing smaller and healthier amounts than they did. We also take care to grill rather than fry in copious amounts of lard as was once done by our grannies and their grannies before them. And so it is, all washed down by a huge glug of Irn-Bru or if you are even luckier, a wee dram or two of the finest malt whiskey. We might hail from ‘Heart Attack City’ but we don’t have to adhere to the lifestyle and habits that has made sure Glasgow has become a worldwide centre of excellence should you suffer a myocardial infarction north of the border. No wonder it is so with the abundance of raw material it has to work with.

But, on this journey home I have no appetite, no need for sustenance or goodies as it feels greedy, feels disrespectful to be thinking of enjoying and spoiling ourselves in the face of the loss of life. I have no unadulterated joy at arriving and catching up with friends and family for how can I when family numbers are dwindling and grief is dominating my every thought and move. The time moves slowly as the miles stretch ahead of us and I suggest we take a break. Mark must be hungry even if I’m not and so we slip off the motorway at the next available services; plastic soulless places where you can buy burgers and chips, stodgy cloying meals that have been left languishing under hot lights for hours that only the very ravenous of people could eat out of desperation or with a serious lack of palate. Nevertheless, with a quick trip to the loo, followed by a weak and tasteless cup of tea and a lacklustre sandwich, we return to the car to continue onwards.

Mark is as downcast as I am for it is his first experience of death at close quarters. “I can’t help but think about my own parents mortality now; can’t imagine what it would be like to lose one of them”, he says trying hard to empathise with what I might be feeling.

“I don’t think you need worry about that too much just yet”, I respond, trying to put his mind at rest “your parents are quite a bit younger than my dad and at seventy eight he’s had a good innings".

“How old is your mother now, she’s quite a bit younger than your father isn’t she?” he looks for a reminder because he can never quite remember.

“She’ll be sixty four in May, in no time at all”, I say, suddenly musing as to what I should get her as a gift this year. It seems unfeeling and trivial to think about birthday presents when there are funerals to be planned but we’re sailing in uncharted territory and life must go on in spite of everything.

Every year that my mother is alive is a gift for only four years previously she had a massive heart attack, one that should have ended her life. As we held vigil overnight in Intensive Care during those first crucial twenty four hours, doctors gave no hope that she would survive the night let alone much longer. But, through sheer force of will and a determination to survive she was hailed a fighter and a miracle woman. What science couldn’t do alone was helped by fortitude of steel from a wee lassie from Glasgow who was certainly going nowhere as her time wasn’t up. Survive she did but so much of her heart had been damaged to the point that she was existing on a cocktail of drugs such as warfarin, an anticoagulant that thinned her blood, making it easier for her heart to pump the blood around her body. But all too often her heart struggles to cope and her lungs fill with fluid when it can’t work as efficiently as it could do. It’s at times like that she is hospitalised and her condition stabilised and she lives to fight another day. My wee miracle mammy; a woman with a zest for life; compassion for others she sees as worse off than herself and a woman deeply in love with her par amour Henry. It is my belief that this deep love she has found so late in life is what keeps her going for I have never seen her so happy to be alive. She embraces every moment of every day and Henry is the epicentre of her universe as she is his.

I am thankful he is in her life because I cannot always be there for her. Work commitments demand so much of my time and it is easy to become selfish and to place my own needs above hers. Too often I claim workload and distance as a barrier to helping when she might need me. Too often I rely upon my sister Fiona to fly in from Luxembourg to do what I should be sharing with her. I convince myself that at least now her family is grown and being a housewife affords her the time to be there for mum. Too often I am simply not in the country and it’s all over bar the shouting by the time get back to the UK to find my sister has once again shouldered the brunt of her care. I help financially but I should do more; offer more practical help but my mother refuses, tells me she’s proud of me and my career and that she wouldn’t hear of me cutting short a business trip to come home “just because she’s feeling a bit under the weather”. Too often I am too ready to believe her and carry on with my life in glorious isolation of her and her problems. But now that my father and uncle have died in such a staggeringly close timeframe, I am starkly aware of how fragile a hold we have on life. I resolve to make more of an effort and put her first at this time of her life. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, ‘it is a tragedy to lose one parent, to lose two is just carelessness’. Providence has given me a bum deck of cards to deal with but in doing so I am reminded of how precious my surviving parent has become to me.

After five hours and several traffic jams our journey is coming to a close and soon I must face the reality of my father’s empty home and my brother’s grief stricken state. Mark tries to distract me as we pass by Uddingston and Daldowie crematorium where my father’s ashes will rest. All too soon we will be here saying goodbye to a man that I am not sure I will miss. Shortly after, we pull up outside my father’s home. My brother waiting eagerly for our arrival steps from the house looking ashen and deeply sad. Once more I am overwhelmed by his grief and hold him tightly in a wretched bid to say sorry, to make up for leaving him to deal with this on his own.

Monday, 7 April 2008

Part 3 - The Catastrophic Effect - A retrospective account

Want to catch up on this story?.............Part 1...............Part 2

The thud of my hand luggage landing on the hall floor brings the cat running to see who’s disturbed his slumber. “Hi little man, did you miss me?”, I say with a smile as I bend down to pick him up for a cuddle. It’s been two months since I waved my goodbyes to him before I headed off to Heathrow airport and onto Minneapolis to complete the final stages of my project. He nuzzles his head affectionately into my neck but I can hear much huffing and puffing and I move out of the way as my partner pushes a ridiculously large and overstuffed suitcase through the front door into the hall.

“Dear god Mob, maybe next time you should ship some of this old crap back instead of trying to take up half the hold in the plane”, he moans at me. He’s red faced and out of breath from the exertion of dragging this monster from the car to the house. I want to snap back at him that quite a bit of ‘that old crap’ as he calls it is several pairs of jeans and t-shirts and a leather jacket all bought for him at knock down prices and all courtesy of the pound being strong against the dollar for a change. I bite back my retort because I know he's tired and because I’m so very grateful that he’s risen really early on a Saturday morning to pick me up from the red eye flight that got me in to Gatwick at 0600am.

It’s been a fairly arduous fourteen hour round trip but I’m finally glad to be home; back in familiar surroundings but I’m immensely disoriented from the time difference and being away for so long. Everything’s the same and yet nothings the same. Northamptonshire couldn’t be more different to Minneapolis but each place holds a special affection for me. A fitful sleep in the car on the way home seems to have left me more exhausted and irritable and I would gladly kill for a deep sleep and some peace for a week. I turn to close the front door and for the first time am captivated by the garden and just how beautiful it is becoming. It’s mid April and the pink and yellow blossom on the trees look stunning and welcoming with their burst of colour. They were bleak and naked when I left in February. I momentarily forget the burden that weighs heavily on me but it returns as quickly as it went. It’s been two weeks since John called to tell me about dad and here I am home, finally home and dreading what is to come.

The cat’s long gone in search of some field mice so I close the door and pick up my hand luggage and head for the bedroom. The familiarity of my own bedroom and knowing that I’ll be curled up there sooner rather than later drops my stress level a notch.

“Stick the kettle on Mark”, I shout down to my partner. There’s no answer so I stroll down to find him looking murderously at the suitcase that needs dragging from the hall to the utility room as I need to unpack and launder my clothes. You’d think he was expected to singlehandedly lug it all the way up Mount Everest rather than to simply move it a few feet. Jeeze he could be a cantankerous git at times but at least he was my cantankerous git.

“C’mon, I’ll push and you pull”, I offer and together we manage to get as far as the sitting room where I unpack the gifts that have been packed at the top of the case. He’s thrilled at the jeans and tops and prances about in his new leather jacket then clears off to see what it looks like in the bedroom mirror.

In the moment’s silence just sitting on my hunkers next to the case, I feel extremely low and overwhelmed and in danger of buckling under. But there’s no time for self pity because I have to get myself together. I’m enormously cheesed off that I didn’t have enough time to launder my clothes before returning home but the project had demanded every waking moment right up until we went live two days ago. Being a week overdue just added to the pressure to deliver, to get the loose ends tied up and come home. But we did it and in relative terms a week was practically a legendary small amount of time to 'go over' as I’ve never seen an I.T. project come in on time, under budget and without problems. I left the USA with my boss’ and client’s blessings and felt that at least my professional world was under control even if my personal world was unstable. “One nil to me”, I told myself.

I knew that John was right and I should have come home two weeks ago but it hadn’t been possible, not at such a crucial stage in the project. There was simply no one else available to guide it to completion. If truth be told I was relieved that the decision had been taken out of my hands. I comforted myself with the knowledge that my father’s prognosis was in months so two more weeks didn’t mean much in the scheme of things. It made much more sense to me to complete the project so that I could spend some time with him without continuous interruptions from work. Much better that than the shoddy alternative of a fleeting visit to say goodbye, a hasty and callous exit from his life and a swift return to work. At least this solution means I can take over from John and give him the break he so desperately needs.

Lord knows I need a break after slogging through seventy hour weeks for the last few months and perhaps spending some time with my father is one way we can put the past behind us. But all of this may be academic; I still don’t know if I want to, or can, be with him. There’s so much to forgive and I’m irresolute that I can step up to the task. Guilt wields a heavy stick over my head as I wrestle with my conscience; guilt at not rushing home to Glasgow as soon as I heard the news; guilt that I feel no emotion about his impending death; guilt that I don’t even feel angry at him anymore. But hey, that’s the thing about us Catholics, we graduate with a first degree honours in guilt and it’s indoctrinated in you from the off and for me it has been nothing but a source of irritation throughout the years. All that bloody fire and brimstone approach to worship leaves me cold but maybe there’s a point to it after all. At least, besides indifference, I can feel something now, even if is just guilt.

Now that I am home my life is taking on a new reality. A six thousand mile gap between Glasgow and me held it all at bay but the nearer I am to Scotland the sharper the focus of the problems I now face. I am but a mere four hundred miles away and ever closer to confronting a dying man and the prospect of that troubles me greatly.

“What’s the plan for tomorrow then?”, Mark asks on his return as he helps me take the laundry I’ve been sorting through to the utility room. “The car’s been serviced and I’ve topped up the oil and water so we’re all set as far as that goes. Are you still sure you want to drive up rather than fly?”

“It’s such a waste of money to fly there and then hire a car Mark. I’ve got two weeks off and I don’t know how long we’ll be there. Best to have the car to get about in so I can see Mum and the others. We’ve got to get between three hospitals don’t forget”, I remind him.

“I know, I know”, he says with an air of resignation. How are your uncles? Have you spoken to your mother and your aunt lately?”

“Mum called me last Thursday. Uncle Iain’s no better and still under observation every ten minutes because he’s threatened to kill himself again". Mark shakes his head at the futility of it all.

Uncle Iain’s life has spiralled out of control since his wife died six months ago and his brother followed suit less than a month later. We’ve always known that he was completely dependent upon Aunt Libby and living without her would be a challenge but we’ve been shocked at his total self destruction and his determined refusal to live without her. It’s been heartbreaking to see his demise but he is hostile to any offer of help and our once mild mannered uncle has become a tortured angry man with only thoughts of suicide on his mind.

It’s hard for me to see my mother saddened at the loss of her older brother and now fretting about her younger brother and his state of mind. The news of my father’s impending death must surely affect her in some way, but when I ask her, all she is prone to say is that she is saddened to hear of his demise but that after twenty years apart, it’s no different to hearing of the loss of an old neighbour. I leave well alone because each of us has to deal with his dying in our own way; each of us has to respect the individuality of our unique relationship with him and what that means to us. I am heartened that at least with this news my mother is coping and not embittered for she doesn’t need more sadness and stress heaped upon her; her heart just isn’t strong enough. I sense that we are at one over his death; she is as indifferent to his passing as I am. On reflection perhaps that is the best we can offer him after years of misery meted out by his hand.

Mark hands me a steaming mug of coffee. “Here drink that, the caffeine should give you a second wind for a while”. I’m too exhausted to hold the mug to my mouth and I rest it on a side table and sink down onto the sofa. I haven’t dared to sit down until now for fear of nodding off and achieving nothing before we leave tomorrow. Mark slips neatly down beside me and wraps a big strong arm around my shoulder. I let out a deep sigh and for a moment I am content just to rest my head on his shoulder and let him carry some of the burden.

“And what about your uncle James too?”, he asks, knowing that this is my Sword of Damocles, causing me deep anguish. He knows the tears that I should have shed for my father are shed instead for the man who has been my mentor, guide and surrogate father figure all of my life. I start to weep as I imagine my aunt and cousin’s agonies as they hold vigil beside his bed; his deterioration from cancer now so evident that it is only a matter of time. But still no one utters a word about him dying; no one talks about it openly. It’s all hushed words and metaphors and we all read between the lines. My aunt and uncle are of a generation where it is sufficient to know what is happening and to get on and cope as best you can. “What’s to be gained from overly sentimental dialogue?”, they would ask, had you challenged them. It’s taken time for him to die, too much time to be in agony as this disease ravages every organ and cell in his body. We’ve come and gone in his life of late, wondering whether each visit was the last. I know in my heart that this time it will be.

It is a hideous situation that must be bourn and I’ve heard it said that God doesn’t give you more than you can handle. Well bugger me for I am certain he’s having a sabbatical and left his incompetent sidekick in charge because how the hell are we supposed to deal with this lot?

My day passes in a haze of domestic activity, making sure we have enough clothes to see us through for a while. Katie my friend and neighbour will feed the cat, water the plants and make sure there’s no stray post hanging from the letter box for opportunist burglars to happen upon. By eight o’clock what needs to be done has been done and I’m finally able to sink deeply into my armchair with a large glass of wine to hand. Mark rolls in with a takeaway pizza and hands me two slices and tops up my wine glass. I’m light headed from the wine and hungry but I don’t have an appetite.

“Eat it , c’mon MOB, no point you getting ill too. You’ve had nothing but two cups of coffee all day and you can’t drink on an empty stomach. You’ll have one hell of a hangover and it’s a long journey tomorrow”, he quite rightly admonishes me. I force myself to eat the pizza and it tastes good and comforting and washes down well with the robust red wine we are drinking. Thank God for Mark. He’s my anchor in stormy seas and I don’t know how I’d get through this if it wasn’t for his empathy and his strong practical approach to helping me.

Comforted by the relaxing effects of the wine and the pizza, coupled with the jet lag, my eyelids feel like lead and I start to drift off into a gentle slumber. The shrill ring tone of the phone wakes me abruptly an hour later.

“Mob? “ . It’s my brother John, calling to check the details for tomorrow I suspect.

“Hi John, how’s it going then?”, I ask him, as I rub sleep from my eye.

“Not so good Mob, not so good”. The line goes quiet as I wait for him to speak. Eventually he clears his throat and says shakily, “dad died ten minutes ago”.

The news leaves me cold, even further detached than before. My brother is crying softly on the other side of the call and I feel shock, confusion and emptiness. I say all the right words to try and comfort John but what use are words at a time like this? Platitudes are imposters, just empty words, masquerading as helpful little sound bites to make the narrator feel better and leave the bereaved no better off for their utterance. But nevertheless, it’s a ritual we must follow if we are to become practiced at grieving and going through the motions. We do our best for there is no handbook to guide us; no mentor to take us by the hand to lead us through the barren landscape of deep anguish, fear, anger, sadness and heartbreak. I know as I end the call with John he will need to find his own way through the maze of grief. Nature must take its course and only time will prove to be the balm needed to mend my brother’s broken heart.

Mark moves to engulf me in his arms and I move in towards the safety that his body promises me. He guides me to the sofa and when we sit he gently strokes my hair and says nothing for he knows it is pointless. I know that he will wait to see what my reaction is and take his lead from there. It seems like an eternity has gone past and we’ve been locked in this embrace for all of it. The shrill ringing of the phone breaks us apart and I run to answer it, wondering which of my siblings it might be; a sibling perhaps as detached as me or deeply upset like my brother.

A voice I didn’t expect to hear greets me in sombre tone. My cousin Joseph is sad to tell me that Uncle Iain has finally achieved his wish to leave this world and to end his mental torture. Exactly forty five minutes after the death of my father, Iain wrapped a wire coat hanger around his neck, attached it to a light fitting and hanged himself.

Overwhelmed by the news, I sink to my knees and start to weep. I wept for the futility of the loss of Iain’s life by his own hand whilst my uncle James battles desperately and heroically to cling to his; wept at the loss of opportunity to see my father one more time; wept at my stupidity and callousness in delaying my return. I simply wept and wept until I ran dry.

I tortured myself that night by listening to The Living Years over and over. Mike and the Mechanics certainly knew a thing or two about leaving it too late and, dear God, I’d just joined their club........

Thursday, 3 April 2008

Part 2 - The Catastrophic Effect - A retrospective account

Want to read part 3?

“Mob, telephone call for you; says he’s your brother but the connection is kinda bad”, a soft Minnesotan accent informs me as the handset is thrust towards me.

“Hello, who’s that?”, I ask wondering who of my five brothers feels it’s important enough for them to call me in the USA. I wasn’t even aware that they had my office number and am momentarily baffled as to how they found me out here at the research and development centre.

“Hi, it’s me, John”, he says in a voice that is echoing down the line making it difficult to hear as each word repeats several times over another and another and another. A further string of words tumble over each other but I begin to make out that something is wrong and that I should come home.

“Dad’s ill, it’s cancer, lung cancer”, he says sounding very matter of fact.

It takes a moment or two before the news sinks in and I feel completely detached from any kind of emotion or reaction. I sit down on my chair and pull myself towards my desk where I rest my head in one hand, buying time before I respond.

“How is he?”, I stupidly ask, but I’m on autopilot trying to absorb the news. “I mean, how serious is it?; is it terminal?; how long’s he got?”. I babble on not knowing what to say or how to say it without sounding crass or unsympathetic. I’ve never been one to beat about the bush and it was typical of me to be logical and straightforward in my approach and this situation was no different. But, having said that, in the past I’d often wondered how I would feel on hearing the news that a parent was seriously ill or dead; had even played a few scenarios out in my head just so I could be prepared for the worst when it came. But shit, none of that came into play now; so much for wasting time getting all sad and emotional and picturing how I’d cope . I hadn’t prepared myself for feeling nothing, nothing at all, not even a jot of emotion.

I heard John's voice as he enquired as to whether I was alright or not and it brought me back from my reverie. “So, what’s the score then?”, I ask again, needing to get a handle on what we were all about to face.

“The doctors are putting a treatment plan together now and I should get sight of that sometime later today. I’ve called the others and told them the same”, he says referring to my brothers and sisters, “but as you are the furthest away, perhaps you should consider coming home, sooner rather than later”.

“Christ, is it that bad then? “ It’s beginning to dawn on me that that perhaps the old boy’s card really is marked and that his days are numbered. But still I continued to feel nothing, not even relief that my father, with whom I have at best a tumultuous relationship, will be out of my life forever. In extreme moments there had been times in my life I had wished him gone; wished he'd never been my father.

“I’m sorry I had to give you this news”, John says forlornly, sounding very weary. “I’ve been here for two weeks now and we’ve only just been given the diagnosis. Seems he had pleurisy and that was masking the symptoms, but from what I can gather, it’s neither here nor there in terms of the outcome. The doctors don’t hold out any hope and the treatment plan isn’t going to be a cure. You do realise what I’m saying don’t you MOB?”, he asked as though what he had already said hadn’t made an impression; that he hadn’t quite got the severity of the situation across. But he’s right to enquire because in the short few minutes that we have connected I have gone from being surprised that my brother has called me here to having to grasp the fact that my father is dying. No doubt in the space of a few hours he has grown from being a novice bad news teller to a consummate professional narrator because he has had to tell eight of his siblings perhaps the worst news he could ever tell them.

“Jesus John, how the hell are you holding it together”, I ask him because I know that he is dealing with this on his own.

“To be honest MOB, I’m exhausted and he’s been so bloody demanding and yet I feel so deeply sorry for him because he’s scared and frustrated. Mostly all I see is a broken old man who flits between bitterness and confusion and I could do with a break; do with some help to take the strain”

The guilt looms large on my horizon; I know that being the youngest brother this wasn’t supposed to fall to him, it was never meant to be a problem that he was left to resolve on his own. Suddenly I feel like weeping, but not for my father, only for my younger brother who is clearly beginning to bend from the task that he bears heavily upon his shoulders. I’m glad of the sudden need to cry even if it isn’t for the right person or the right reason. At least I feel some kind of emotion and that’s finally normal isn’t it? If I didn’t know better I could swear that my heart is going to burst out of my chest and I feel faint.

“Look sweetie, I know you understand that there is little I can do from here right now. You know what I think of the old man and how he feels about me. But, I’m not sure how I feel about this right now and I need time to come to terms with what you have told me. Well, at least I need time to sort out my workload – get someone else to take over my project”.

I know it’s a cop out and that I’m bailing out on him but I can’t face this right now; can’t be bothered to dredge up the past and to deal with it all head on. It’s too late, much too late....

“Okay, I wasn’t expecting any more and don’t beat yourself up about this”, he tries to reassure me. “I know what the score is and I’ve got things under control but to answer your point about how long?; a few months, that’s all and that’s more than likely an optimistic figure so don’t go leaving it too long” . He knows what I am like with work and how I bury myself knee deep and loose all track of time. This is his way of making sure I register that time is short, there won’t be any extensions or flexibility on this one because nature doesn’t work like that, it doesn’t do deals and nor will it fit in with my schedule just because I demand that it does.

We bring the call to an end and I promise to call him tomorrow to find out where we stand. He’s relieved to know that at least I love him enough to care about him and I suppose he’s hoping that some of that empathy might just stretch to my dad as he lies fighting for his life while his strength ebbs and flows with natures tides.